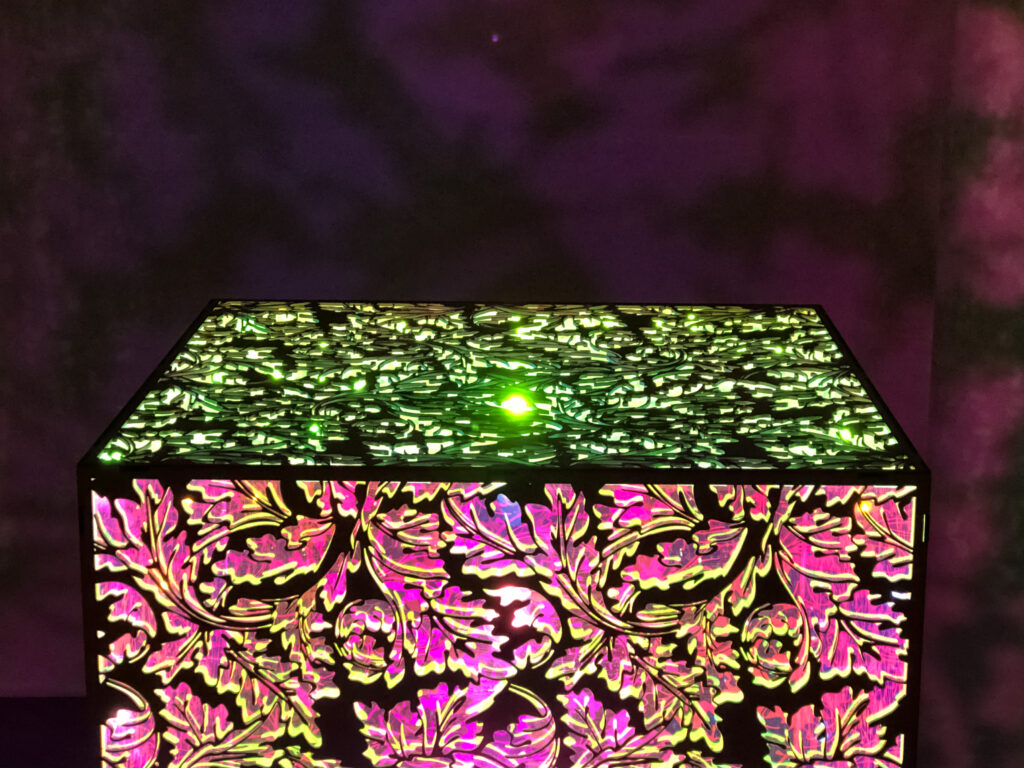

sham–real shadows 2.0

A laser cut mdf cube, cut in negative of a flatten acanthus leaves historical wallpaper design by William Morris. Lit from within, the pattern pushes forward in positive onto all nearby surfaces. Version 2.0 features a dichroic micro-prism interior box that causes the colours of the cube to shift depending on a viewer’s angle to any flat side; as the light is static the projected colours are as well, however the pattern bounces off of the prism film in unexpected way leaving a main pattern on the wall that is yellow, orange, purple and pink, with a secondary echoing pattern that is blue and green. This crafts a shadowpaper that falls on the surfaces of the space including the viewer.

in a pink mist

Trevor Van den Eijnden

2015–2020

laser-cut paper and MDF, embroidery string,

10.2×10.2×10.2 cm

From a soul is not made of atoms; text by curator Dr. Adrienne Fast

“sham–real shadows is a project that developed out of the familiar strangers, and which takes these ideas a step further. The work consists of an acrylic and wood sculpture set in the centre of a square room. The structure is laser cut in the pattern of William Morris’ acanthus leaf wallpaper pattern—possibly his most famous wallpaper design—from 1874. At the apex of the Industrial Revolution, Morris created highly stylized designs like this one in response to his contemporaries who strove for what he considered to be overly naturalistic patterns. Morris rejected attempts to reproduce the natural world with verisimilitude, calling such patterns” … sham-real [branches] and flowers, casting sham–real shadows.” 2 In Van den Eijnden’s work, Morris’ comments become the catalyst for an immersive polychrome experience. By illuminating the laser cut pattern through micro-prism film, the walls of the room are transformed into a wash of pattern and colour, that the artist calls “shadow paper.” Here, again, the viewer is an active participant — the pattern literally falls on our bodies as we view the work. The intertwining of nature and human is complete.

For Van den Eijnden, the transformation from object to shadow is also particularly important. Shadows can be conceived of as a kind of echo of a real object, in the same way that a designed representation of nature is a kind of echo of nature itself. But Van den Eijnden would argue that, in our current world, we do not have access to an unfiltered or unmitigated experience of nature; there isn’t a square inch of the planet that hasn’t been affected by nuclear fallout, for example. Although a shadow or a representation is not the “real thing,” Van den Eijnden’s work suggests that the mitigated experience can matter in its own right – it may be qualitatively different, but it is no less real. He hopes that by bringing together in these works a kind of tension between nature, and human design, and art, there is a new space opened up where we can appreciate the interconnectedness of all three, and where viewers can have a joyful, even a spiritual response, to something that isn’t “true.”

sham–real shadows also functions as a pivot point in the exhibition as a whole. The twilight effect of the coloured “shadow paper” on the walls of its self-contained gallery room functions as bridge between the bright daylight space occupied by the super saturates, and the dark, dreamlike space that contains the final bodies of work in the exhibition. In this way, just as the individual works in the exhibition reference our experience of the passage of time, the exhibition as a whole references the passage of a single day as we move from daylight to darkness. In the final, darkened spaces of the exhibition, visitors encounter several bodies of work that combine the dominant themes of the artist’s practice: an exploration of our relationship with nature — and related experiences of ecological grief — and also our relationship with time, and the forging of connections between past, present, and future.”

2 William Morris, “Some Hints on Pattern-Designing,” a lecture delivered at The Working Men’s College, London, December 10, 1881. Published by Longman & Co., London, 1899.